Healing, Trust, and Reconciliation in Healthcare

- Watermark Health

- Feb 27, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 28, 2025

As we come to the close of Black History Month, we pause to reflect on a sobering reality: for many African Americans, the healthcare system has long been a source of deep mistrust. The painful history of medical injustices—ranging from the Tuskegee Trials to the abuses against Black women in early gynecological research and the unauthorized use of Henrietta Lacks' cells—has left scars that still impact Black communities today.

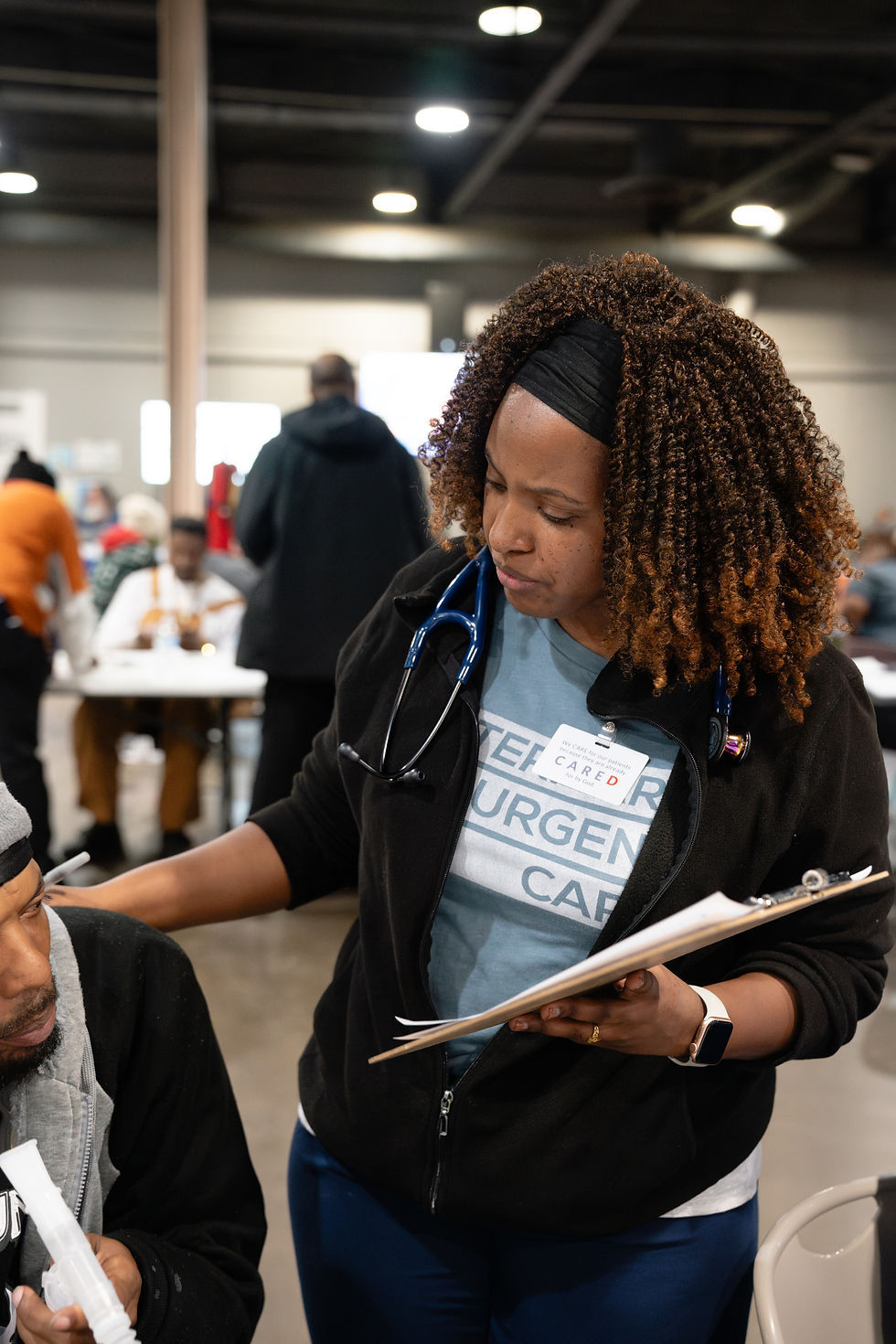

Recently, a group of our staff and volunteers discussed these injustices and how we, as a Christ-centered healthcare ministry, can be a place where trust is restored. Our mission is deeply rooted in the truth that every person is made in the image of God (Genesis 1:27). This means that every patient who walks through our doors—regardless of race, background, or financial status—is seen, valued, and worthy of compassionate care. And because Christ is at the center of our work, these issues matter to us.

At Watermark Health, we believe that reconciliation is not just a good idea—it’s a calling. 2 Corinthians 5:18 reminds us that God has given us the ministry of reconciliation. That’s why we do more than just treat symptoms; we take the time to listen, to sit longer in patient rooms, and to truly care for the whole person. Not just because we're compassionate caregivers, but because we follow a Savior who deeply cares for all people.

The Power of Representation and Listening

We are continually encouraged by the leadership of our Medical Director, Dr. Providence Okaalet, who shared her reflections on Black History Month:

"As I reflect on Black History Month, I think about how my experiences as a Black female doctor in Kenya and America have shaped me. In Kenya, I am part of the majority—there’s no doubt about my belonging. In America, I am often the only Black woman in the room, facing challenges that extend beyond medicine.

In Kenya, my presence as a doctor is unquestioned. Patients may be curious about my background, but they trust my expertise. In America, reactions vary. In South Dallas, Black patients celebrate my presence, telling me, ‘You’re my doctor? Well done!’ But in central Texas, where most of my patients were white, I often got surprised looks and skepticism. ‘Oh! You’re the doctor?’ they ask, as if I need to prove myself.

In America, I constantly have to affirm that I’m not just a doctor—but a qualified one. Patients, families, and even colleagues sometimes question my legitimacy. I’ve been mistaken for food service staff and assumed to be a lab technician despite my white coat, name tag with credentials, and stethoscope. These moments are frustrating, but they also highlight the barriers Black professionals still face.

Despite these challenges, I find strength in representation. When Black patients see me and feel inspired, I know my presence matters. If even one young Black girl looks at me and thinks, 'I can be a doctor too,' then the struggle has been meaningful."

Restoring Trust Through Intentional Care

Representation is only part of the equation—true reconciliation happens when we listen and provide care that restores dignity. Patient Miriam Fields shares her own experience:

"I do have some issues with the healthcare system and how we’re treated—we’re treated like we are at a manufacturer going through the assembly line. You get seen for maybe 10 minutes. You may get the answer to what you need, you may not. But when I go and see Dr. Providence, when I go to the Urgent Care at Watermark South Dallas, I am not rushed… I am not pushed out. And that’s what we need. We need people who are going to hear us."

The Reality of Health Disparities in Dallas

Unfortunately, racial health disparities are not just a thing of the past—they are a present reality in our own city. According to the 2022 Dallas County Community Health Needs Assessment:

Life expectancy is lower in predominantly Black and Hispanic communities than in wealthier, white neighborhoods.

The rate of uninsured adults is highest in communities of color, making access to consistent medical care difficult.

Black women in Dallas County experience higher rates of maternal mortality, often due to systemic barriers in healthcare access and bias in medical treatment.

There are entire neighborhoods in South Dallas classified as healthcare deserts, where residents have little to no access to nearby medical providers.

These statistics are more than just numbers—they represent real people, real families, and real lives affected by inequity. That is why our work at Watermark Health matters. Because we believe that the gospel compels us to respond to these disparities with action, advocacy, and deeply compassionate care.

Moving Forward Together

As we reflect on Black History Month, we are reminded that justice and reconciliation are not just social issues—they are kingdom issues. We press forward with the hope that our commitment to Christ-centered healthcare will continue to break down barriers, restore dignity, and be a light in communities that have long been underserved.

For those who want to learn more, we recommend two insightful books:

The Accommodation: The Politics of Race in an American City – A powerful look at racial history and policy in Dallas.

Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism – A deeply personal exploration of race and medicine from the perspective of a Black physician.

Divided by Faith: Evangelical religion and the problem of race in America - a historical look at the impacts of racism within the church and how the Gospel provides a solution

The Church and the Racial Divide - a bible study focusing on the biblical view of why God cares for all people and how racial reconciliation is a gospel imperative

May we, as followers of Christ, never grow weary in the work of reconciliation. Because every patient we serve is made in the image of God—and that changes everything.

Comments